Mapping invisible cities

Three strong trends that are appearing all over the world in multiple domains:

- What gets mapped or measured gets noticed. What doesn’t, “disappears.”

- Adjacent idea; various entities, like large corporations and some government instances try to obfuscate issues and information to dissimulate parts of systems.

- Data is everywhere, being collected everywhere, and often seized or made private when it should have been public and transparently available.

In this piece at MAS Context, Olga Subirós explains how these three trends and other factors interact and why it’s important for citizens to create and collect cartographic evidence of invisible cities.

There is data sovereignty, which we must demand from the public sphere, and also the data we can produce from active citizenship. The aim is to redraw the city by creating new cartographies to support the best analysis and diagnosis to resolve our coexistence and guarantee the right to a just city.

When thinking about maps, most people think of terrain, roads, and buildings, but much more than those can be mapped.

Mapping the invisible in the city means putting what is ephemeral on the map. The city is, above all, invisible activity: the data on telephone use, social networks, banking transactions, the consumption of basic supplies, check-ins at restaurants and leisure venues, complaints, etc. and also environmental data such as air quality, water and soil quality, noise pollution, etc. This represents huge amounts of data and metadata.

As alluded to in the three trends above, often what’s not shown on a map is as important as what is. Every decision to map or measure something is also, by definition, a decision to ignore something else. Those decisions are always political, and those politics often influenced by vested interests, like corporations.

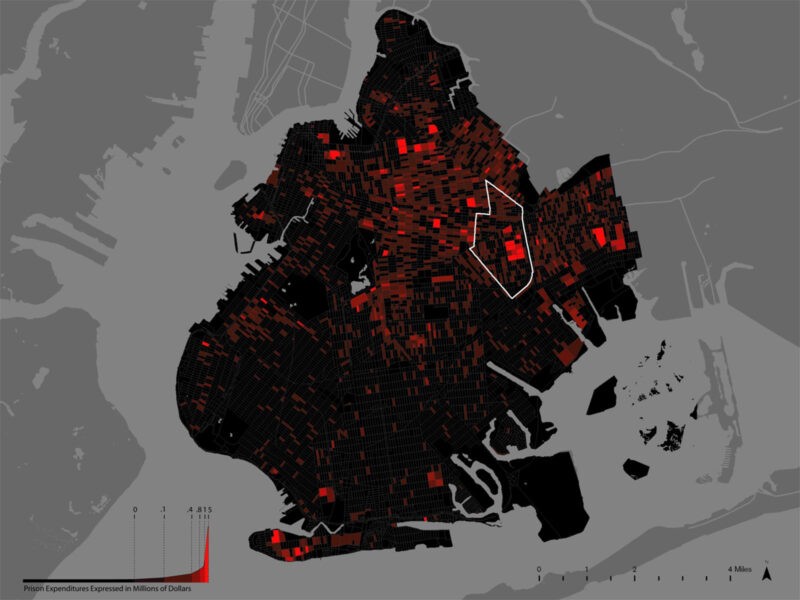

Mapping “the invisible” means mapping everything that we don’t see, everything that has been left off the map. What is it, exactly, that isn’t being mapped? What is it that we aren’t showing that allows systemic inequality, social and environmental injustice to continue? […]

Constructing cartographic evidence is a political act. Deciding what we consider to be sufficient evidence is also a social construct. This type of cartography is not a mere representation of data; it becomes a presentation of proof. Proof that takes on sufficient authority to question, point out, denounce, to demand responsibilities and changes in the regulations.

After setting the groundwork for how mapping can be a powerful tool, Subirós lists and details a number of great projects and organizations doing that kind of work, tracking things like: community justice, spending on incarceration; conflict urbanism; human rights violations; evictions; and programs that enable citizen to participate in mapping projects.

The conclusion connects these efforts with two important issues: what should a smart city actually be, and fake news.

Because a “smart” city is one in which citizens use data to diagnose its problems. It is urbanism using big data for the common good as a tool to uphold the social contract, a tool that complements citizen participation. […]

At a time when fake news has become widespread and sectors of power persist in denying the crimes that are committed, the creation of evidence is a fundamental tool for citizens to combat exploitation, systemic inequality, and mass surveillance by governments and corporations.